Waxhaw’s Robbie Smith is a family man, operator of his own business, and an outdoorsman. He grew up in this area hunting game birds and fishing with flies, and he knows the land and story of this state better than just about any Carolinian you’re liable to come across. He’s a normal enough guy…aside from the fact that he owns an ungodly amount of wooden ducks.

Yes, Robbie collects old duck decoys. In recent years, he’s amassed a library of relics from all over the state, carved by immensely talented artisans who had no clue they were artisans, these North Carolina watermen who called our coasts home. And he’s not alone in his obsession: Decoy collecting is more than a hobby for some of Robbie’s peers. At the right auction, the right bird can go for hundreds of thousands. That’s not hyperbole.

For some people, this hand-carved wooden duck was the foundation of their existence, what kept them alive.

Wild waterfowl provided an abundant source of food for settlers of the North Carolina coastal regions, and early residents were known to make these decoys to lure the birds within range of their guns. But why, today, is there such acute interest in these old wooden things? Well, like anything made necessary by the demands of a tougher time, they have something to share.

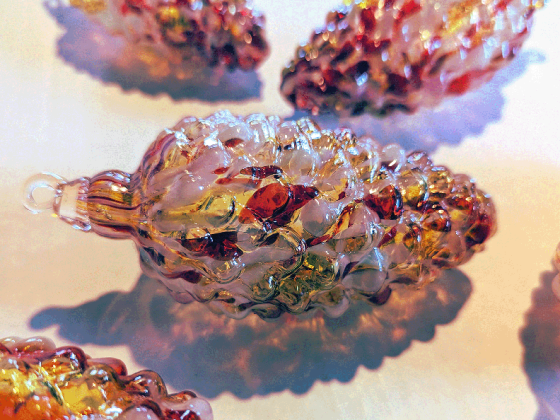

“The decoy is a handcrafted tool,” Robbie Smith explains. “It was used to create a living for somebody, whether it put food on the table or allowed these coastal folks to cater to hunting parties. For some people, this hand-carved wooden duck was the foundation of their existence, what kept them alive. And they just happen to be incredible pieces of art: The patina of a 120 year old bird that has the original paint, the form and the sculpture of it… There’s not much like it in our state.”

They are beautiful, each duck varying in size and shape and material according to their varying origins. They’re usually small enough to hold in one one’s hand, but counties like Currituck and Dare yielded bigger and blockier birds: Because of the enormity of the surrounding sounds, hunters needed large, obvious decoys. The carvers of Hyde County, meanwhile, used the limited mediums available to them in their swampy region, crafting beautifully crude, organic-looking pieces known to collectors as “root heads.” Some areas along the coast are even known for their shorebird decoys, tiny beach robins and willets designed to be staked in the sand, though these are exceptionally rare today. Some of the most striking decoys in Robbie’s collection are the wire frames, decoys whose form is stretched and painted canvas: These things have a geometric quality to them that makes sense to the eye—maybe the wire skeleton is an attempt to mimic nature’s frames.

It’s odd: When a bunch of these things are collected together, they betray a kind of history that isn’t written down anywhere. It seems Robbie Smith isn’t just collecting beautifully rendered pieces of wood. As he sought out the underbelly of decoy collecting—to the dismay of his wife Leslie, who’d just found some small mercy in his fly-rod-collecting lull—something sparked. With every new acquisition, the decoys seemed to lose their woodenness.

“At some point, it all came to life for me,” Robbie recalls, wide-eyed.

Well, the ducks didn’t. They’re made of wood. But each of their roughly hewn lines and battered tails and buckshot-ridden heads started to show distinct character. They started to reveal their makers, and in turn, their makers’ stories. Every new decoy brought with it some tale of a time before now.

“I started to want to know things about the carver,” Robbie says. “Where was this guy born? What did he do for a living? Did he serve in any wars?”

Robbie can tell you a hell of a lot about a man who lived nearly a century ago by looking closely at one of his birds. Like any collector, he’s got his preferred artists. Lee Dudley of Knotts Island is known for his majestic canvasbacks. Dudley was one of few North Carolina carvers to use glass eyes in his designs—a trend common among New Englanders—and most collectors can spot a Dudley duck a mile away. No respectable history of decoy carving excludes him. Stacy’s Mitchell Fulcher seems to have had the steadiest painting hand of all Carolina’s carvers, as his pintails are some of the most stylish, graceful birds in the state. Like many of his ilk, Fulcher was so poor he could rarely afford brushes. Fortunately, the chewed end of a gum tree branch usually did the trick. Robbie’s personal favorite, James Best, carved some of the most beautiful fowl decoys found in Kitty Hawk or anywhere. Widely considered the finest carver from North Carolina, the man was a veritable classics sculptor: With the cleanest of lines and symmetry that appears to have taken days to perfect, these birds are true fine art. Ironically, this duck-carving prodigy didn’t hunt many ducks.

In the 1920s, you needed something to do. If we were those guys, we’d just sit on the front porch and carve some decoys. We’d talk, sip a little liquor, and then carve some more decoys.

Robbie’s favorites often tend to be the hardest to find (and purchase), but that’s the nature of any obsession with antiquities. A lot of factors inform a duck’s value, from the skill of the carver to the date of its making. The combination of original paint (decoys were often repainted to reflect which fowl was in season) and an original head (these were known to disappear often due to, well, 10-gauge shotgun blasts) fetches a hefty sum. They were used and abused, so a largely undamaged bird is extraordinarily valuable. In large part, though, these things hold such value because of their rarity. They’re not really made anymore. The practice of decoy carving all but ceased in the latter half of the 20th century, and there’s no real consensus as to why. Industries evolved, and automation in manufacturing may have played a role, but Robbie thinks people just got distracted. Television and radio came along. But when you weren’t working in the 1920s, Robbie says, “you needed something to do.”

“If we were those guys, we’d just sit on the front porch and carve some decoys. We’d talk, sip a little liquor, and then carve some more decoys,” Robbie grins, as if he knows he’d be welcome on that porch.

What is a collector? Robbie Smith doesn’t carve decoys. He’s not an artist, but he understands an art. He sees in an old thing value where others may see only gathering dust. He even sadly admits that he’s not sure what will become of his collection when he’s gone. But it’s not just the learners, the studiers, and the curious among us who give these old things their worth: Their value is ingrained. North Carolina is part of these wooden birds, and they have stories carved into them. And when Robbie’s no longer here, someone else will care.