A tribute to J. Charles Jones Esquire, The Freedom Riders, and the many others who were catalysts in integrating Charlotte and the South. – On a chilly Sunday morning I stand in line at a crowded coffee shop on Trade Street, in the Third Ward of Charlotte. As I wait for my morning cup of coffee, I take a look at who is around me and can’t help but notice the different people. It’s a cultural melting pot, and no one seems to notice. Weaving through the crowd, coffee in hand, I can’t help but think about the differences a few decades have made. These people, who now coexist peacefully, would not have been able to do so fifty years ago during segregation.

For many people, segregation is known only as a word written in history books, speaking of a racial divide that defined generations before them. Segregation, by definition, means to separate or set apart from a main body or group. However, by simply reading the definition of the word, we lose the true meaning. To those whose lives were defined by segregation, it was much more than a simple separation; it meant the loss of basic rights and human dignity. And by “rights” I’m not speaking of the right to vote or freedom of speech, because during this period in history, these privileges were reserved for whites. What I am referring to are the simple things we often take for granted such as the right to take public transportation without having to sit in a section according to skin type, to drink from the same water fountain as everyone else, and to eat lunch at a counter that was, back then, reserved for “whites only”. In fact, that very injustice fanned the flames of a movement that would change the course of history.

It started with four young, black students from A&T University who decided to take a stand, or ironically, a seat at the lunch counter of Woolworth’s department store on February 1, 1960. Franklin McCain, David Richmond, EzeIl Blair, Jr., and Joseph MacNeil sat at the whites-only lunch counter and politely sought service. They were denied, but their strength and courage to seek equal treatment inspired thousands to take a stand and begin the sit-in movement; the very thing that changed Charlotte’s history.

There is a spirit of strength that settles among those who have taken part in changing history. That very spirit is settled over Charlotte; home to leaders who have not only changed the city but have taken part in shaping the path of our nation. It is a unique and humbling experience to make the acquaintance of such a leader. Even more unique is a meeting that starts with the feeding of fish.

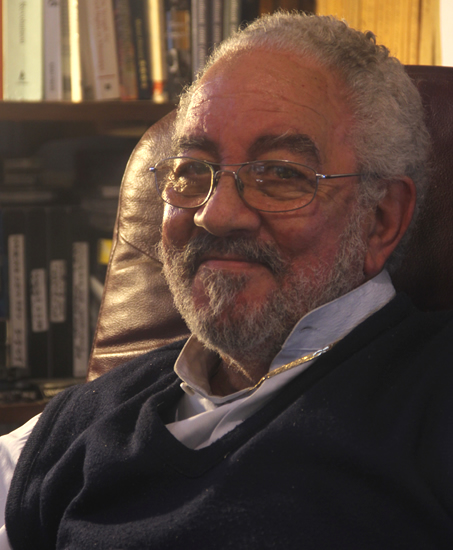

Koi fish are fascinating creatures. A Japanese symbol for perseverance in adversity and strength in purpose, it is no coincidence that they should be a part of my first interaction with civil rights leader J. Charles Jones. Dressed in a black turtleneck sweater vest and slacks, he warmly welcomes me and my colleague ushering us into the greenhouse, which he has constructed as an alternate power source for the home he and his wife Jackie have spent years developing.

As he hands us both koi food pellets, a smile stretching from ear to ear, he tells us that on the count of three we are going to toss in the food. He then addresses the fish as he would his dearest friends, bids them good eating and on cue, we toss our rations into the pond. As the fish feast, Jones’ gentle warmth emanates throughout the room and, in almost a whisper, he tells us that our spirits are now a part of his home and that we are welcome to enter.

Taking a seat in his office, I can’t help but feel an overwhelming sense of reverence for the history surrounding me. Posters of freedom fighters, news articles, law books, and family photos adorn the walls. As he takes a seat in the rich leather chair, I am at a sudden loss for words and unprepared to ask this man, who has seen so much, to tell me about his life. As if reading my thoughts, Mr. Jones begins to speak.

He begins our meeting with a humble prayer inviting the ancestors, Jesus, Buddha, Allah, Dr. King, Gandhi and his great grandparents who were born slaves, to surround us with style, wisdom and grace, and to help us walk our paths with wisdom, inspiration and compassion. His rhythmic prayer is heartfelt and a chill creeps over me as I imagine the ancestors’ presence.

As he finishes, I find myself in awe of him and once again I am speechless so I say the only thing I can think of, “If you don’t mind, we would like to hear your story.” Fortunately, that’s enough for him and we are thrust forward into a journey of courage, dedication, pain and ultimately, positive growth.

In the early 1900’s, slavery was a way of life for most African Americans. As the world evolved and developed, slavery was abolished, but segregation lasted well into the 1960’s until the Civil Rights movement. Well known are the stories of Dr. Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks, whose courage moved a nation to desegregation, but lesser known are the stories of local heroes like Jones who found himself in a unique position to become one of the leaders of a movement that would change Charlotte indefinitely. It started with the recognition that something needed to change.

Jones grew up in Chester, SC in a totally segregated community. “I never had a sense of being different. My father was a Presbyterian preacher; my mother was an English teacher, and as children, we would shoot marbles and have fun. However, we knew there were clear lines. For instance, there was a fellow named Jonesy, who had an IQ of maybe 64, who shuffled along kindly and Daddy would get him to help dig the garden and do chores. There was a day, when I was about six, that Jonesy had been accused of smiling at a white lady uptown and the word was out that they (the Klan) were going to get him. So my father and his friend put Jonesy in the trunk of the car with some food, and they drove off. I didn’t understand it at the time, but they were saving him from being lynched – just for smiling at her. I began to realize the harsh consequences of not obeying the rules.”

Jones grew up in a well educated family and quickly learned how different he was treated because of the color of his skin. With the strength of his grandmother who taught him to, “…stand up tall, speak in proper English, look people in the eye and don’t think you’re better than anyone,” he quickly realized his mission to speak out against segregation and the need for a non-violent movement for change.

February 1, 1960 Jones, a student at Johnson C. Smith University, was on the way home from participating in the National Youth Summit Conference in the Soviet Union when he heard a news report about the four young black students from A&T college who sat at a whites-only lunch counter at Woolworth’s department store politely requesting service. It was just the encouragement Jones needed. He quickly convened a meeting with the Vice Chair of the student council and student body in Biddle Hall and announced his intentions to go to Woolworth’s the following day, dressed in his “go to meeting, and a little sweet water” with the intention not to leave until they opened up for service.

“That night I remember thinking, ‘Oh man, what have I done?’”, but the spirit of his ancestors encouraged him and the next day he did as planned. He anticipated a handful of students waiting to join him but was surprised to find over two hundred had gathered in the hall, “…ready to rock and roll.” So that’s what they did. They started at Woolworths and took over all of the street level lunch counters in Charlotte.

Jones, familiar to the press for his participation in the Youth Summit, was questioned by reporters. When asked, “What is this all about?” he simply responded by quoting the Declaration of Independence, noting, “We are going to be here every day to point out the contradictions between what you claim you are and how you behave. I’m standing here dressed nicely, speaking intelligently and nonviolently, but I can’t get a hot dog and sit at the lunch counter to eat it. What’s up with that?” And from that point on, the why of what was happening with the student sit-ins became the focus. They would not accept the word “no” any longer. The sit-in movement spread nationwide. In July of 1960, the Charlotte sit-ins gained a foot hold with department stores seeing a severe loss in sales. Just two weeks later Mayor Brookshire arranged for pairs of black and white business leaders to eat lunch at “upscale” restaurants and progress began to take shape.

Jones’ spontaneous laughter erupts again as he recalls, “We organized a boycott. Don’t shop where you’re not respected. Then we were joined by a number of white people on the picket line. They became very integrated. People started to realize how crazy this was.”

In late July the boycott became intense. Department stores decided that because they were losing money they were going to do the “right thing” so they wouldn’t have to file bankruptcy. Two days later the mayor called Mr. Jones and informed him that the bi-racial committee had negotiated an agreement with the merchants on the street level.

Jones quiets, the ghost of a memory passes before his eyes and in a hushed tone recalls, “He said to me, (Mayor Brookshire) ‘You can go quietly tomorrow and be served without any fanfare or problem. ‘ And so the next day my father and I went down to the lunch counter at Leggett’s department store. The waitress smiled at us and took our order – I got a tuna fish sandwich and Daddy got a hot dog and a Coke. And coffee, some of the worst coffee in the world – and we were sitting there, quietly eating and Daddy looked at me and said, ‘Son, I’m proud of you.’ And I looked at Daddy and said, ‘I’m proud of you. Thanks for the lessons of when to hold ‘em, when to fold ‘em, when to take a stand but also when to walk away.’ And we sat there and finished quietly. It was Leggett’s food but it clearly had a sweeter taste because we had earned the right to sit there.” It was a step in the right direction for Charlotte.

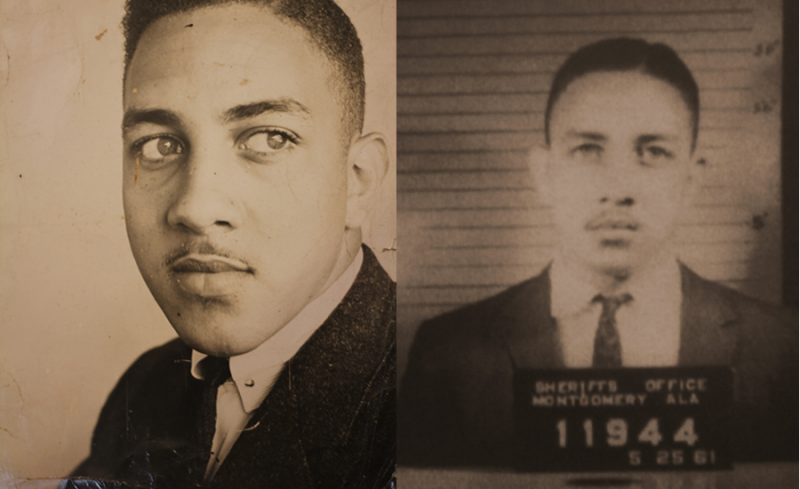

Seeing the need to help elsewhere, Jones and a few friends traveled to Rock Hill on January 31, 1961 to sit-in with students from Friendship Junior College. The group, later coined the Friendship 9, made a pact to sit-in, got arrested and did jail time on the chain-gang. They served time at York County Prison Farm shoveling mud from the river banks. Jones brought their ‘Jail, No Bail’ form of protest back home with him. Their dedication to nonviolence made Charlotte one of the most peaceful areas during desegregation but even so, there were times when Jones and his friends questioned their own safety.

Clearing his throat, he quiets for a moment and then recalls, “Around 1962 in Terrell County, Georgia we were trying to get people to register to vote. So we had this meeting way out in a rural church one Saturday night. Twenty people had come quietly, like slaves would steal away after master had gone to sleep, to meet. We were at the meeting and there was lookout checking to see what was happening around us. He came in and said ‘The Sheriff’s out there with the head of the Klan, and the Marshal is out there taking tag numbers.’ Everyone knew what the taking of tag numbers meant. It meant that at any point you could just come up missing. Just then the sheriff slammed the doors of the church open and yelled, ‘This is an illegal meeting. You know we’ve got your tags. Break this meeting up now.’

Jones looks me squarely in the eyes, tears welling up and begins to rock gently in his chair. “There was this older lady, in her early sixties. She started rocking and singing.” And as he recalls this woman’s haunting song he begins to sing the words, “Oh freedom, oh freedom, of freedom over me. And before I’d be a slave, I’ll be buried in my grave.” Tears streaming down his face, he clasps his hands together and rocks in the chair, “We all started singing with her, ‘And go home to my Lord and be free.’ And the old woman stood up, continuing to sing and walked out of the church. The sheriff ushered us out as we were singing, yelling at us to stop. As she walked by the sheriff he quieted, and we didn’t hear any more from him.” It turned out that the old woman had been the midwife that delivered the sheriff out of his mother’s body. She had nursed him from her own breasts, taught him life’s lessons. She had raised him.

“I was so inspired by that sister,” he says as he wipes the tears from his cheeks, “because that was a combination of the experience of slaves, the negro spiritual songs, the pain and the humility. When that sister stood up,” he shakes his head and sighs, “we were afraid because you knew at moments like that there was a possibility you could be plucked out.”

It would be a few years until desegregation was complete but, with moments like that to reflect on, the city began a slow evolution. Leaders made a conscious decision to respond to what was happening and to be as rational and non-violent as possible. Schools saw integration, Charlotte became one of the first places in the country to integrate the busing system, and one day at a time, the city formed itself into the progressive, diversified banking city that it is today.

Jones’ journey has led him through some of the most dangerous, racially segregated places in the nation. He has traveled to different countries in his quest for peace and equality and along the way, he has encountered many influential people. He shared jail time with Dr. King, crossed paths with Bobby Kennedy and was even a guest on the Oprah Winfrey show during a special segment on the Freedom Riders.

He continues to inspire generations through motivational speaking, his law practice and through rallying the local community to keep the streets clean, neighborhoods safe, and students educated. His plight is one for the sake of diversity, love, peace and human connection, to build a beloved community, and through his actions, along with the guidance of his ancestors, that is exactly what he has accomplished.