Bob Timberlake likes to share, and he’s done a lifetime’s worth of it. Internationally acclaimed realist painter and steward of the United States’ most successful furniture line in history, he is a living embodiment of the American Dream. His body of work, meanwhile, is a dream of America. Bob’s vision of his homeland is nostalgic, but not mournfully so, retrospective without forfeiting all the good in the present. It’s a world in which weathervanes still advise and roosters must crow, in which farms are farmed and roads lead only to other roads. It’s a time he’d like to tell you about, anecdotally, if you have a few hours and a taste for some Carolina barbecue.

With paint, with wood, and with fable, Bob Timberlake tells a story of America. His myth of our nation wouldn’t exist, though, without a myth of himself. Both stories, incidentally, begin with a Revolution.

Less than a month after the United States won its independence, on the night of the second of November, 1781, two friends were assassinated in modern-day Davidson County. These men were killed at the same moment, in their respective homes, by a group of Loyalists. The fighting had ended, but they were murdered because they had raised all the arms in this area, helping to build the force that would fight for General Greene in the decisive Battle of Guilford Courthouse. They’d lost that battle, but crippled much of Cornwallis’ army in the 90 minutes of gunsmoke chaos, laying the groundwork for the British surrender at Yorktown.

Valentine Leonhardt and Wooldrich Frits were among the battle’s survivors, until that cold night in November. These patriots were buried shoulder-to-shoulder in a common grave, while the Colonel who’d led them into battle, a dear friend of both men, gave a eulogy over their graves: “These two men, who have lived together, fought together, and died together, we bury as one soul—as is our nation because of them.” Bob Timberlake is descended from the first of these men, and his wife Kay is descended from the second. The Colonel, who eventually brought their murderers to justice, is an ancestor of Bob’s boyhood friend.

“Yeah, I’d say we’re from here,” Bob smiles, recalling this Lexington lore. “Those two souls are one in our children,” he says, misty-eyed, “and we don’t take that lightly.”

A modern-day patriot armed with creativity and amiability, Bob treasures origin tales like this one. But Bob isn’t just from this little furniture and barbecue town; he’s invariably part of Lexington, North Carolina, a facet of its culture and its community, and he believes he could never have been otherwise. For him, heritage has always been the highest form of education, the most formative chapter in his story.

“Everything I do comes from a love of where I’m from,” he shrugs. “People always want to know where I got this gift, what kind of training or education I’ve had, but all of my training came from right here. I guess you gravitate toward what you love. I just did it. I still just do it.”

Indeed, Bob seems to have always found a way to just do the things that interested him. His first furniture design was a Pennsylvania Dutch dowry chest, which he painted at 14 years old. It won a Ford Motor Company-sponsored industrial arts contest that sent him halfway across the country, a dreamlike trip for the talented little boy from Hillcrest Drive. He wouldn’t set his mind on furniture again until nearly forty years later, but working with his hands was suddenly a religious hobby.

At his mentor Andrew Wyeth’s suggestion, Bob devoted himself to his art full time at 33. He’s been painting professionally for nearly 50 years now, and with absolutely no formal art education. In ’81, after exhibits all over the country, he’d become the the only Southerner in modern history to hold a one-man exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C. In 1990, he launched a furniture line based on his own handiwork, and its overwhelming success engendered a fully-fledged brand.

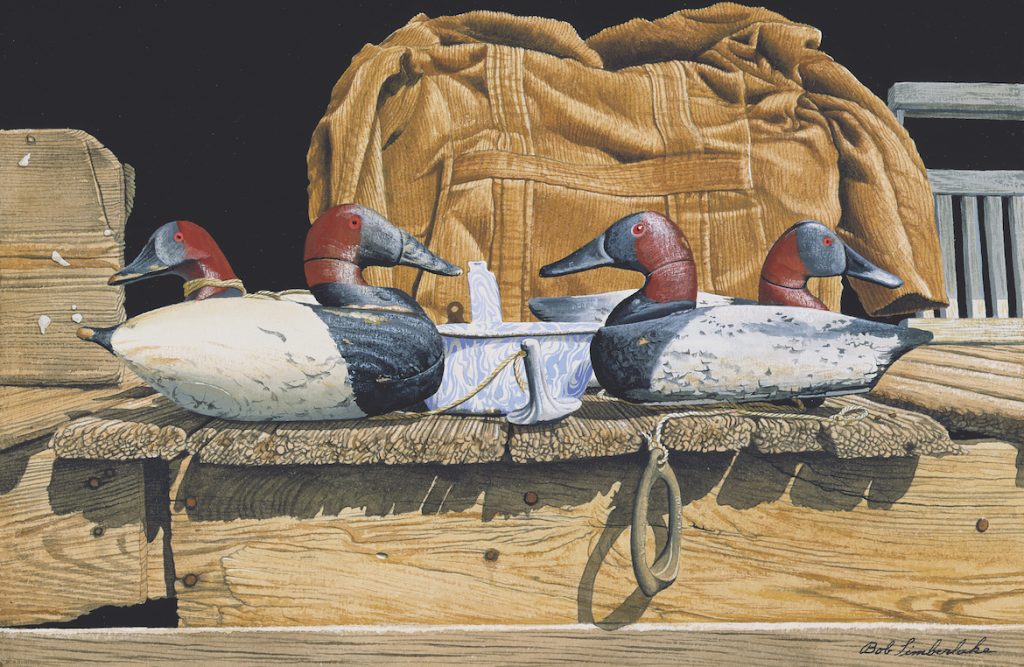

An avid hunter and fisherman, Bob’s love of the sporting life is, like his paintings, a result of his all-too-healthy obsession with the natural world. In the seventies, he began a long-term partnership with anti-litter campaign Keep America Beautiful, one of the country’s most well-known and successful public service announcements. A man who’s spent the better part of 79 years preserving Carolina in watercolor probably couldn’t help but be a conservationist.

Today, the man and his brand are a household name, especially in Carolina. It’s one hell of a story, but if Bob is to be believed, it wasn’t all put down by him. Bob Timberlake—as well as everything for which he’s known, by extension—is a product of his surroundings.

“There’s always been someone prodding me along,” he chuckles, “someone nurturing me, in this town.”

He learned a “heck of a lot under cars” with his older brother.

“Tim carried me hunting, fishing, and even carried me on dates with him,” Bob reminisces. “He kept me humble too: I didn’t know a chicken had white meat until I was 21!”

But the eldest of the Timberlake boys was just one of many influences.

“Everything I am, I am because of my brother and my dad, because of the fella that taught me how to fix things, because of my friend John D. Locke, because of my aunts and uncles a few blocks away on 1st Avenue,” Bob explains. “I would’ve never reached puberty if not for these people who showed me things.”

When he was little, this little town taught him “how to grow up.” And ‘little’ is just the way he likes his southern Piedmont residence.

“We’re five minutes from anything,” Bob says. “Probably the most famous pimento cheese in the state is down here at Conrad & Hinkle.”

The same family has owned that store for nearly a century, and they still deliver. It doesn’t get much quainter than this. Lexington Barbecue Festival, a yearly pilgrimage for some 200,000 pulled-pork highbrows, has been named among the top one-day festivals in the country. Every other day of the year, the locals are free to devour their hushpuppies and red slaw, uninterrupted. Everyone’s got their favorite place in town, but they all agree on one thing: “There ain’t no Lexington barbecue outside of Lexington.”

The barbecue joints are as much of the town’s identity as the tomato-and-vinegar-sauced meat itself. One can get anything done just by sitting down in one of these faded red booths.

“You can walk in here and get your car repaired, your yard mowed, your plumbing fixed,” Bob laughs. “It was a heck of a way to grow up.”

There’d be no Bob Timberlake without Lexington North Carolina, and so Bob has never seen any reason to leave Lexington for good. He’s travelled, sure, but he always ends up back in his favorite seat, at his favorite dining spots, eating his favorite barbecue (and he’ll probably have it chopped). He’ll leave just the way he came: “You don’t go out a door different from the one you came through.”

And why would he? The beauty of Lexington won him his initial fame. His oral tradition of America began right here in the rolling hills of the Piedmont. All the best storytellers are skilled framers, and Bob is no different. He captures scenes—both still and emotive, their colors both vibrant and muted—and he invites viewers into them. His stories are just as inviting: It’s a curiosity, but no mistake, that his calling card is an old-world writing utensil rather than a paintbrush. Kicking back on one of his luxuriously-cushioned, oak furniture sets and listening to a Carolina history you can’t find in textbooks, you want to step into his America. His rhetoric tells of a great nation a couple hundred years ago and a great one a couple days ago. In Bob’s mind, we stood for something in our infancy, but we also stand for something now.

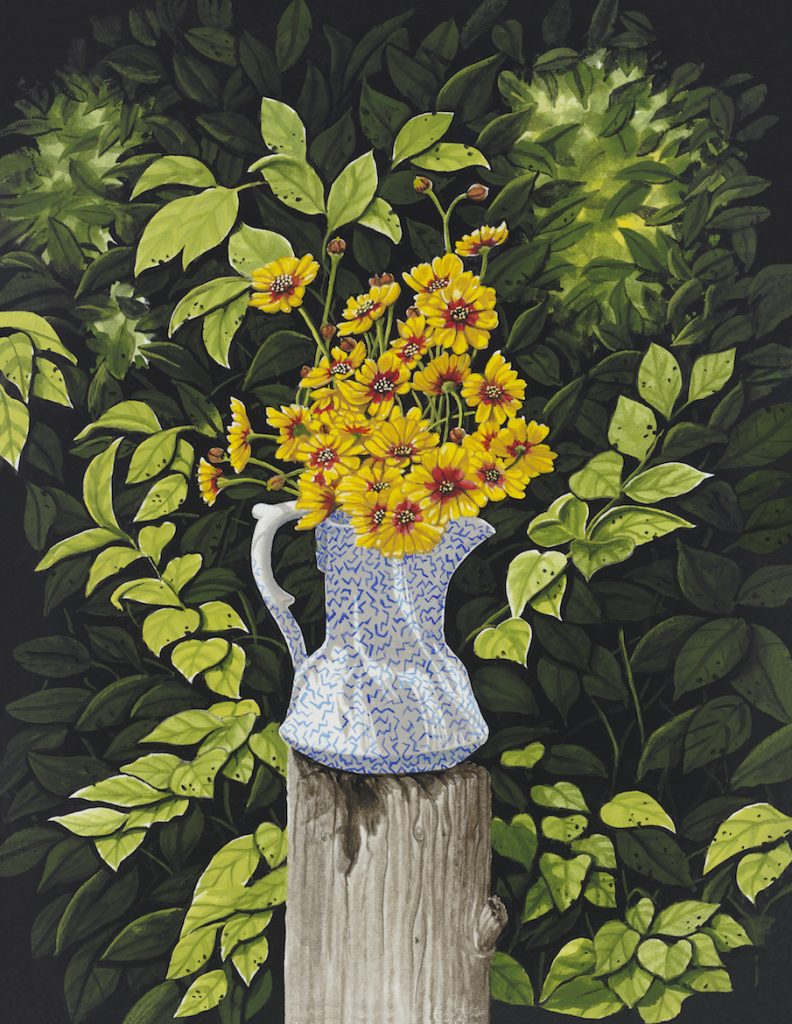

His optimistic perspective of our nation is abundantly evident in the Lexington Bob Timberlake Gallery, a sprawling, two-story panorama of Bob’s life and times. Within these walls, folk can walk right into his story. Designs taken directly from his earliest watercolors are woven into rugs and other pieces of his home collection, hanging from the walls like tapestried history. Bob surrounds himself with relics of an uncomplicated, rural world: decoys and birdhouses, enamelware and quilts, canoes and fly rods. Bob’s gallery is his frame of mind, open to the public. The gallery is also his office and a bit of a regular haunt for him. It’s probably pretty surreal for those walking through this man’s life to actually encounter him, but for Bob it’s just an encounter with people who share in his passions.

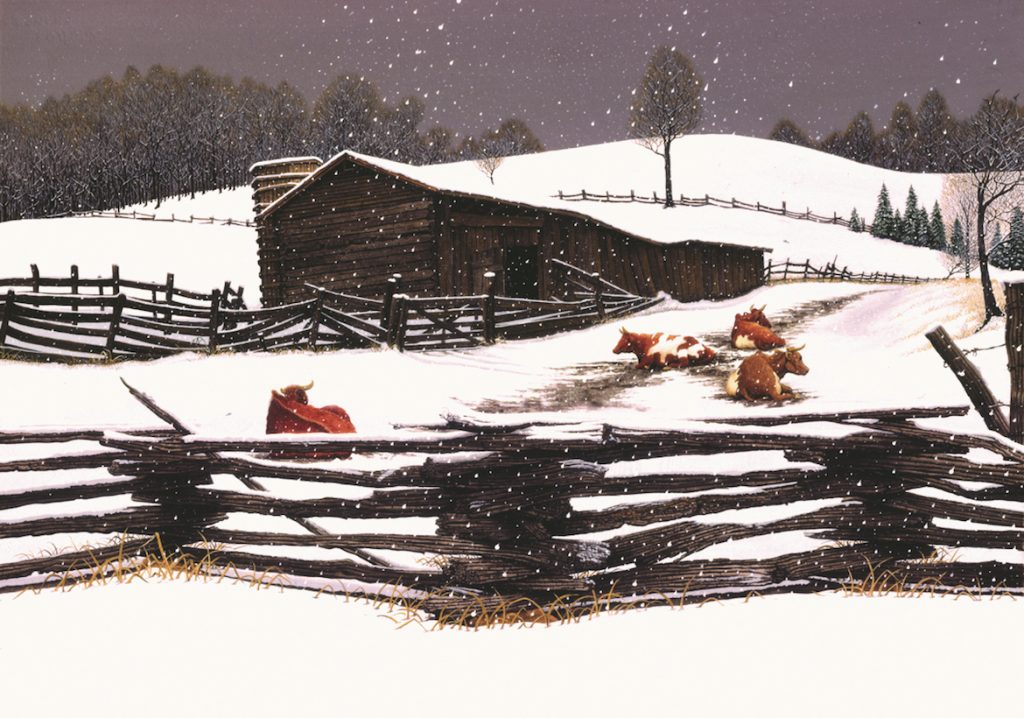

If his gallery is an exhibition of his world, then his ‘studio,’ a whopping 127 acres of beautiful Carolina green, is his world. The three and a half buildings here (including the outhouse) have served as inspiration for hundreds of watercolor masterworks, and for good reason. Everything on this picturesque compound—which was planned, detail for detail, by Bob himself—has a story. The barn-turned-living space, in particular, stands as a monument to the resilience of rural folk. It would’ve been burned down by Yankee soldiers 150 years ago if not for a bold farming woman and her children. It’s just one of many things Bob’s heard to tell of.

His depictions of the simple life speak, almost spiritually, to millions of admirers about the lifestyle they love. His paintings nostalgically recall times from his past, but their subject is not necessarily a time past. Bob’s work is unique in that it’s a celebration of things that are timeless: His landscapes and studies of old buildings aren’t windows into a lost world because that world still exists: “You just have to know where to look for it.” This old America will persist as long as front porches are furnished with rocking chairs, as long as snow quietly covers farmhouses, as long the sudden flight of a covey exhilarates—as long as we as a people still find beauty in the empty field.

Lexington, North Carolina, like any town in this great state, is full of fields and rife with stories, and Bob Timberlake is just their chronicler. A raconteur with an easel, he’s one of the great American fablers, and he’s got plenty more to do before he’s done.

“I ain’t even told the half of it,” he protests when his listeners have to leave him.

But we’ll be back for more. We have to be. After all—it’s a shared story.