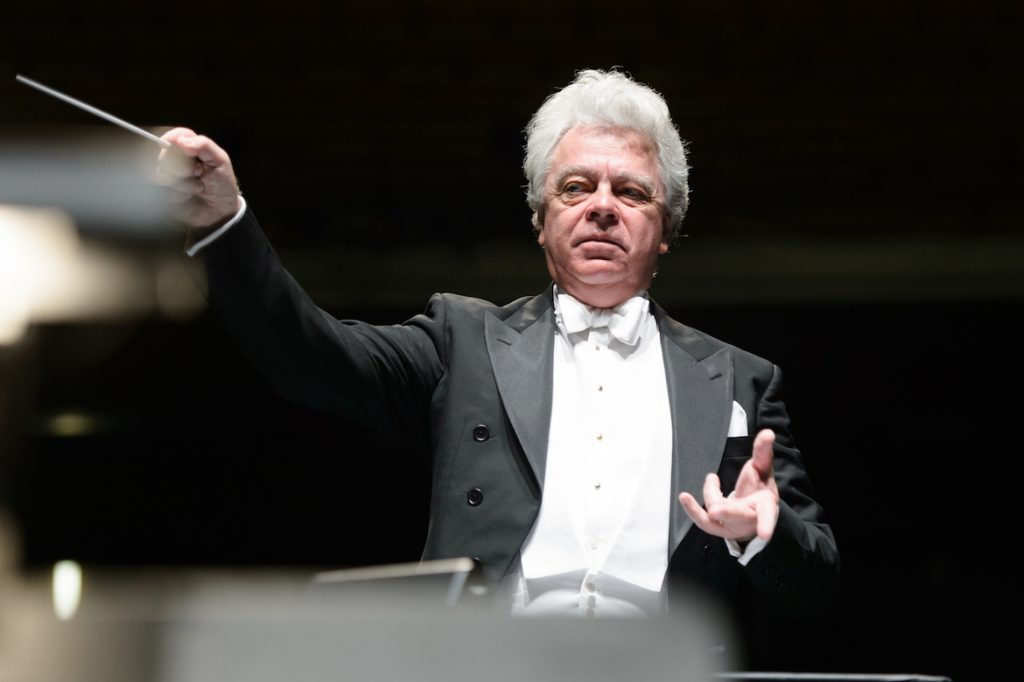

In the first part of our interview with Music Director Christopher Warren-Green, he told us a bit about his origins in England, his efforts to make the symphony more accessible to a wider audience, and how the classics function as a necessary part of every education. In this, our second part, he details what Charlotte and its very American optimism has meant for his career. He discusses differences between his London Chamber Orchestra, the Charlotte Symphony Orchestra, and his experiences guest conducting all over the world. Before it’s over, he’ll probably have another eloquent thing or two to say about the timelessness of the arts and the glaring necessity for them in our every day. His always-delicate cadence doesn’t hide a fierce belief in the significance of his art. It’s all a bit intimidating, but it doesn’t have to be. Have a seat, and just listen. Let him explain.

Despite your fears of long-windedness, I actually would like a brief lecture on the art of conducting. What are the various ways in which you prepare for a performance?

Oh Lord—how long have you got? You have to be able to read a score, but really you have to learn it, to know it. You’ve got to have it memorized; this [motioning toward sheets of music] is just a reference. You’re reading every instrument of the orchestra as it’s playing. You’ve got flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, four french horns, three to four trumpets, four trombones, percussion, first violin, second violin, and so on all the way down the page. So I’ve got to know who plays where and when, to make cues…but that’s not the be-all, end-all of it. The most important thing is that a conductor inspires people. He enables them to give it their hearts, to play from their hearts: To prepare for that a conductor has to be wholly prepared—he cannot make mistakes. You can tear down an entire symphony orchestra, 76 to a hundred musicians and a choir, and you can knock it over like a house of cards by doing something stupid. The trouble with the profession, though, is that you can only learn it in front of an orchestra. That’s why I say you only really mature when you hit 60. You can’t practice in front of a mirror with a record on. It doesn’t work like that. It’s the easiest thing in the world to do badly, and it’s the hardest thing in the world to do well.

Is there anything in particular about Charlotte or the Carolinas that has inspired you?

Absolutely, but it’s really an American thing. It’s this whole American “can-do” attitude, which I just hope you all never lose. It’s something that I really aspire to and that thrills me. Even down to walking into a shop, and the greetings you get: “A wonderful day out, isn’t it?” You don’t always get that in Europe. [laughs] At first, a lot of Europeans think [of Americans], “Oh, come on—you’re faking this.” But you’re not. You’re really not. People are sincere in their positivity. I’ll walk into Blumenthal, ask one of the employees how he’s doing, and I get this “I’m great!” I’ll say, you know, that’s good to hear, and then I get, “Yeah, I’m great. I love my job.” And he means it. He really means that, and this attitude has really affected me in my work. Maybe it’s a southern thing. I don’t know. I’ve been here six years, so I’m Anglo-American now. I’m actually part Welsh, by the way, which I suppose is why I ended up a conductor. The Welsh are a ferocious, fiery people.

So the city’s been good to you. What do you think sets the Charlotte Symphony Orchestra apart from other orchestras, namely the London Chamber Orchestra?

They’re two very different orchestras. A chamber orchestra, by definition, is smaller. The core is the same, the core of the classical period is present in the chamber orchestra, but you are limited in repertoire. Throughout the years, the orchestra got bigger and bigger with the more recent composers’ additions. With a chamber orchestra, you can go as far as Beethoven and Brahms, if that makes any sense. So with a symphony orchestra, you have the full orchestra, all the time. There’s much more scope in repertoire. One is an Aston Martin and the other is a Cadillac. One is a big machine and the other is a compact luxury. The conducting styles are slightly different as a result. You can only conduct a certain way with a big orchestra. It’s like turning a juggernaut, as opposed to turning a sports car.

In addition to manning these two, you travel around the world, guest conducting. In what ways do you approach guesting at orchestras differently?

When you’re a guest, you never have the feeling you have with your own orchestra, and that’s why I love being a chief of my own orchestra. Eyes are the most important thing in conducting. You give cues with your eyes. Woodwind players always look up before an entry. They’re counting on me in their periphery, and I have to be there, ready to bring them in with a nod…or my eyebrows. You can’t always count on that kind of communication with a guest orchestra. With your own orchestra, you know which performers have a tendency to be late or early, which one of them loves to rush the ends of phrases, and you conduct accordingly. By the same token, they know me. They’ll look at a certain part and they know how I like that kind of thing to be played.

That factors into the coalescing or “gelling” you mentioned earlier, right?

Of course. The real fun of this job, for me, is building that relationship. You’re very much a part of the orchestra, the concertmaster (Calin Lupanu, in the CSO) is the pivot between you and the orchestra, and all the principal performers are like lieutenants. It’s a bit like being admiral of a fleet, with a captain, and lieutenants. There’s a regimentation to it. The better you know this thing that you’re part of, the better every performance has the potential to be.

Since you’ve been here, what has the distinct presence of a symphony orchestra meant for Charlotte and the Carolinas?

The symphony is just one part of something bigger. I think that people, public officials especially, don’t really understand what the arts do for a city. This is the orchestra of the city, which elevates the city. It’s like a cathedral—In England, a city has to contain a cathedral to call itself a city. Returning to our discussion of education, consider the number of students who are going to do better in school because of their exposure to a fully realized art community here in Charlotte. Say these students stay in Charlotte, they get good jobs, and they’re making, I don’t know, 40,000 a year. In ten years, how much is that? They’re putting that money into the city. That happens simply because you’ve got a symphony orchestra here in the city. I’ve had lots of talks with the Charlotte Chamber of Commerce, and I’ve got loads of stories supporting that, but I won’t go into those details. It’s been proven over the years that students (of any age) studying the arts—all the arts—alongside the sciences, do better in school than the ones just studying the sciences. So why the hell do governments think, why have they always thought, that it’s a good idea to cut the arts? Every time there’s a recession, the first disciplines that get cut are the arts. They do it in England, in the U.S., and all over the world. They haven’t always succeeded, though. After the Second World War, Winston Churchill was asked that old question: “Mr. Prime Minister, you know, there’s a real shortage of money—should we cut the arts?” And Churchill replied, “Cut the arts? Why do you think we fought the war?” Churchill’s answer is the answer.

An eloquent man—not unlike yourself.

Yes, well, please credit that bit to Churchill. I’d rather not steal his words. [laughs]

So here’s the big one: In what ways do you keep a symphony orchestra relevant in 2016?

Times have changed. Obviously, in Mozart’s time, there was no technology like we have today. Before the second half of the last century, music existed in a room where there were musicians. There are really two questions here—what do you do to make it relevant, and is it relevant? I think the second question overrules the first, and my answer to it, of course, is “yes, extremely relevant.” There was a project in Brazil, years ago, that offered free meals to impoverished children if they could sit through a music course. They could come and eat as much as they wanted, but they had to attend class in order to do so. Eventually, they started coming to class for the class. The food was a perk. One of the kids who wandered into this project was a nine year-old bus gang leader. He had a gang of nine year-olds and he was robbing buses. He was successful—very dangerous, in fact, and the authorities couldn’t catch him. When I met him, he was 12 or 13, hadn’t robbed a bus in years, and all he wanted to do was play saxophone. And he was brilliant at it. If that symphony orchestra hadn’t been doing that…you get the idea. So when people ask, “well, we need more hospitals and more prisons and more means of dealing with these ‘at-risk’ people—how can we possibly put money into the arts?” So many seem to think that the arts are just entertainment, that they’re expendable. My nine year-old bus gang leader is evidence that they’re not. If we actually cherish and nurture the arts, in education especially, then perhaps we wouldn’t need so many hospitals and prisons. We need to get the message out there, to let the uninitiated know what we are. People think that it’s all shiny chandeliers, lofty concert halls, and period costumes.

People think it’s above them, but it’s for them.

Right. It’s a spectacle, but it shouldn’t be threatening. It’s like a live rock show—always better than the recording. There’s something unique about the vibration of instruments in the room. The audience is part of that shared experience. The art is not selfish: Music exists in the hearts of the audience, and that’s where we have to put it, as interpreters. We take this great composer’s work and try to play it in a such a way that it touches people’s souls.