Have you heard of East Fork Pottery yet? Let’s start at the beginning. Despite an upbringing filled with the finer things of the art world, Alex Matisse has an acute fondness for dirt.

He grew up in Groton, Massachusetts, with a family of artists and a childhood saturated with artistic legacy. He’s brother to a Seattle photographer and a New York painter. He’s son of artist-inventor Paul Matisse and sculptor-poet Linda Hoffman. He’s the grandson of notable art-dealer Pierre Matisse, and the step-grandson of Marcel Duchamp, one of modern art’s boldest thinkers. He’s also the great-grandson of French painter Henri Matisse, whose expressive, colorful paintings rank among the most influential and treasured 20th century works this side of Post-Impressionism.

But none of these things define him.

His family of artists is part of him, sure, but in the way those first few brushstrokes are irreversibly only part of a painting — they don’t determine the finished product. He’s far more attuned with the hum of the earth — the soil of the Catawba Valley, the ground make-up of Cameron, North Carolina, and the dirt composition beneath Asheboro — than he is with his famous fine-art family ties. Alex Matisse is a potter. The stuff he makes, he makes for Alex Matisse…famous great-grandfathers or no.

He discovered North Carolina, a state unfamiliar to him, while nurturing an all-too-familiar state of mind. In his formative years, this New Englander was searching, as many young artists do, for what he would be, what he would make. He hadn’t been in Carolina long before he, like many young artists also do, dropped out of school: “I was pretty miserable at college until found myself in a ceramic studio,” Alex recalls. “And that was it.”

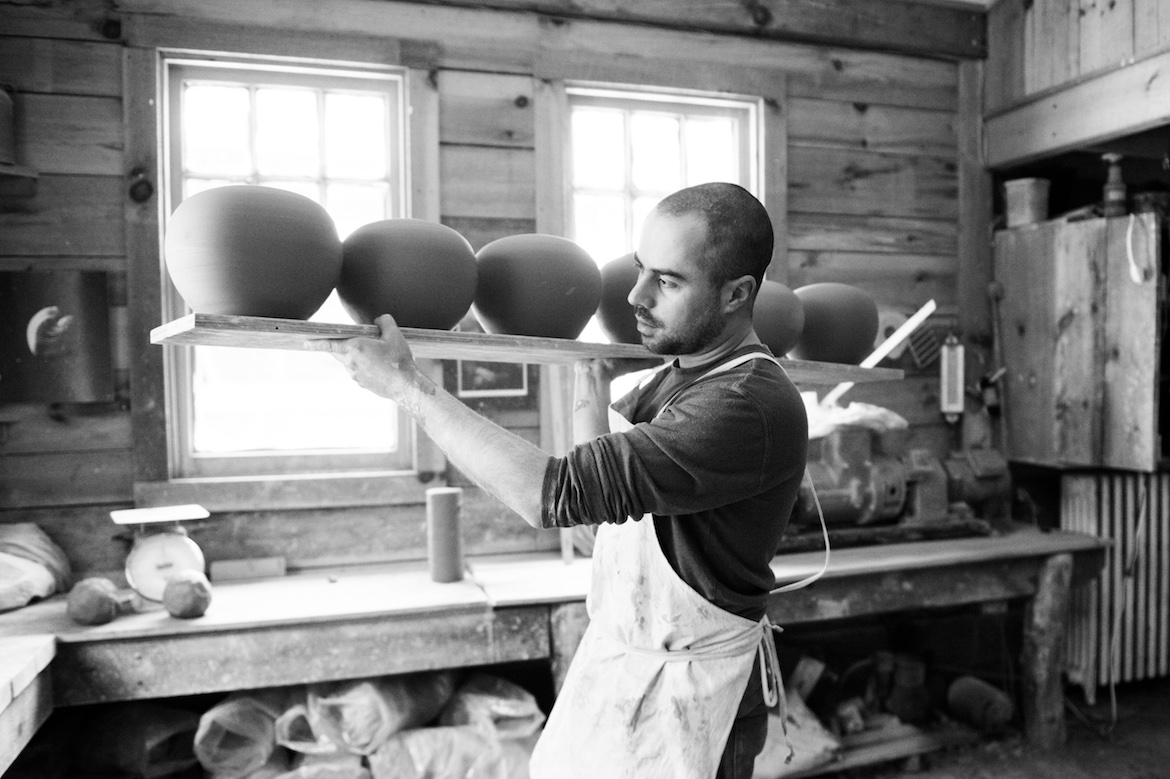

Having found this thing that would be his, Alex had to pursue it in earnest. His schooling quickly gave way to another, decidedly more hands-on type of education. He began apprenticing under North Carolina potters, “learning to replicate his teachers’ work a thousand times over,” an intensive, three-year-long lesson in clay-throwing precision. It was a career choice every bit as difficult as it sounds, a concentrated instruction perhaps more rigorous than any he could’ve found behind a desk.

I was pretty miserable at college until found myself in a ceramic studio. And that was it.

But Alex graduated. Several years, a marriage, and little baby girl later, Alex is now a working potter, a title that seems in its very nature multifaceted. Within his pastoral compound hidden amongst the hills of Madison County, Alex is father, husband, and dinnerware-furnisher. He and his wife Connie Coady have crafted an idyllic life on this old tobacco farm, complete with a locally-sourced diet that rivals even the tastiest of the neighboring Asheville eateries. Alex is also teacher, guild-founder, and brick mason: He actually built East Fork Pottery from the ground up. His massive wood kiln, the climax of several thousand pots’ creation (and occasionally the instrument of their destruction), was built, brick for brick, by him. The only thing out here not handmade by Alex and Connie, it seems, is the old farmhouse, but the property’s pragmatic cosiness is definitely of their making. Somehow, Alex Matisse also finds time to makes pots.

And the whole pot-making endeavor is ever-growing: Alex is partnered with potter John Vigeland, who functions as a sort of CFO to Alex’s creative director, while Connie handles the entire communications end of the business. With ten people on the payroll, East Fork is expanding in several directions. There are now five people “with hands in the clay,” and the business will see the opening of its first brick-and-mortar retail location in Asheville this holiday season. These developments represent what Alex calls a “striking change from a business model that was originally just me in a farmhouse,” but there’s been little departure from the core philosophy of Alex’s business.

A lot of my pots are so tied to North Carolina. They’re so part of this whole vernacular that I can’t see them in a context outside of the Southeast.

The work of East Fork Guild, headed up by Alex and John, represents the original product — one-off, fine-art works right out of North Carolina’s decorative past. Most are gorgeously earthy in color, browns and greens and reds and golds that can’t help but compliment the rustic landscape the Matisses have made their home. And these aren’t your flimsy farmer’s-market arts-and-crafts: Every artfully-glazed bowl and mug, every flower receptacle and sculpture-like vase is imminently safe to touch. They’re made in North Carolina, for North Carolinians, and that’s all Alex wants them to be. “A lot of my pots are so tied to North Carolina,” Alex muses. “They’re so part of this whole vernacular that I can’t see them in a context outside of the Southeast.”

But that’s why the Guild and its accompanying wood kiln are only part of the business. These days, the dexterous hands at East Fork are focused on producing a line for their shiny new gas kiln, and a new, more utilitarian and universal sort of art. While their bold, decorative work champions our state’s artisanal ceramics legacy, this recent foray into streamlined production refines it. The simplicity of the branding, “East Fork Collection,” is apt: The line retains Alex’s core philosophy — “the material integrity and regional sourcing” upon which East Fork Pottery is founded — but molds it into a simpler, more fundamental ware. “This product,” Alex insists, “is resistant to trend—timeless, durable.”

This product is resistant to trend—timeless, durable.

He’s not wrong. Everyone needs plates, and cups, and mugs. And in expanding his work outside the decorative realm of ceramics, this New Englander is actually rediscovering this quintessential Carolina craft’s roots. His repurposing of Carolina pottery is actually a return to the craft’s original purpose. There’s a special kind of art and beauty to be found in that. A Yankee had to come south to show us our roots.

Scored and slipped, his legacy is now inextricably adjoined to Carolina earth, his livelihood aligned with the state’s earliest craftsmen. Alex is a Carolinian, in the most archaic sense. Even the floor in his studio is dirt.