What makes America?

Depending on who you ask (and when, and where…) you might get some very different answers. But that’s always been part of the beauty of this country: There isn’t really one America, and when you can believe that, well, it all opens up.

Sometimes we need a reminder of the multiplicities these United States contain. Someone or something to push us outside our comfort zones, someone to expand our idea of what we think is “normal.” And really, outside of art, there are few other things that can charge right into your very own living room and bring you face-to-face with the unusual, the unknown, the previously unseen.

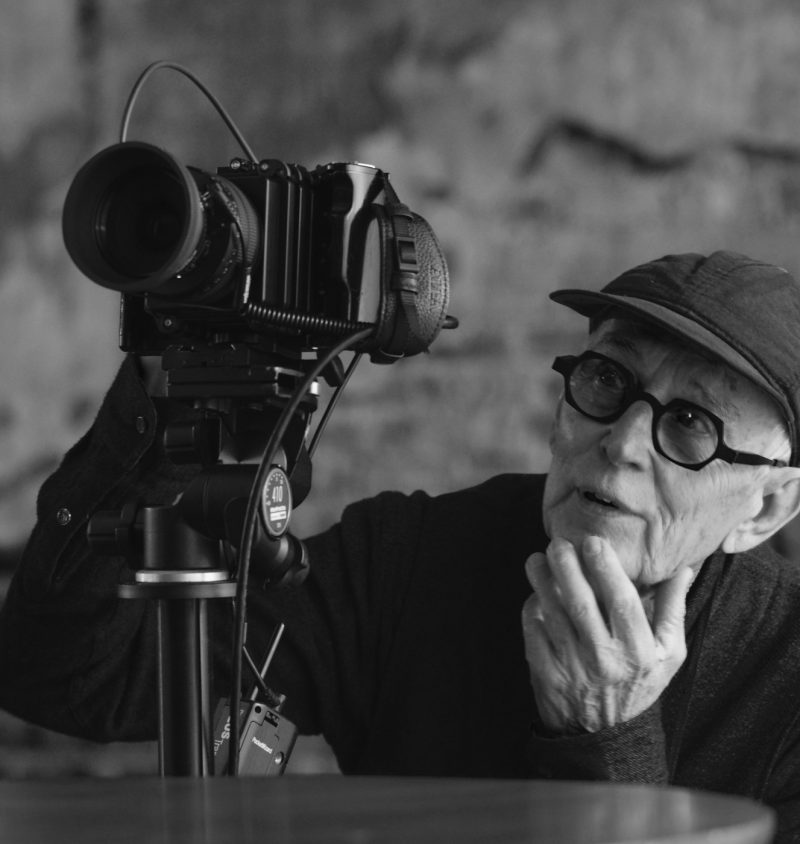

Burk Uzzle knows this. He’s entirely captivated with our country. As equal parts documentarian and visionary, Uzzle has fiercely dedicated practically his entire life to preserving a view of the States that is at once entirely his own and somehow also universally recognizable. From his stark images of today’s South, captured now that he’s returned to his home state of North Carolina, to the iconic revelry he documented at the 1969 Woodstock, Uzzle did, and still does, what few can with a shutter and a lens.

As Vicki Goldberg, in her foreword for Burk Uzzle’s Just Add Water, put it, “[Burk] has conducted a visual love affair with America for years… He sympathizes with her bad moods, her tragedies, her rather glaring imperfections, her obstreperous beauty, her unlikely aspirations.”

The man is a true photojournalist, award-winning with a prestigious pedigree, and a real artist, single-minded in his devotion to his craft. He produces prints with a sort of composition and nuance that often closely mirror fine art on canvas.

“Photographers hold a heavy responsibility as we shoulder the capacity to optically convey information,” he says. “We don’t always do that well. My belief is that so-called documentary photography is, in fact, incredibly subjective. How can it not be when we chose where to stand, in which direction to point the camera, and when to click the shutter?”

Uzzle poses this query in that signature contemplative manner of his, which, to be clear, is a disposition well-earned. In 1962, when in his early 20s, Burk became the youngest photographer ever hired by LIFE Magazine. He was a member—and two-time president—of the prestigious international Magnum photo cooperative. So this is just how Uzzle lives, by this point in his career: Political and aware, he’s a man who takes the ethics of that lens very, very seriously.

Born in Raleigh in 1938, the eldest of four children, Burk Uzzle first started taking photographs with a cheap little Kodak box camera as a teen. His parents were less than thrilled with his preoccupation, but Uzzle was characteristically undeterred.

“Back in those days, no one took photography seriously, but it’s the only thing I’ve ever loved,” Uzzle recalls.

He sold his prints to state newspapers, and with that money and the padding of paper route income, Uzzle soon graduated to a Rolleicord and 4×5 Speed Graphic. Through the countless hours spent finessing his craft and chasing down images, Burk Uzzle launched himself into his first career position as photographer at The News & Observer of Raleigh.

That gig was what landed him LIFE, a position he calls a dream come true.

“My tenure there provided the worldly education I denied myself by avoiding college,” Uzzle explains. “The extraordinary variety of assignments and places coupled with the magazine’s demanding high standards kept me enthralled. I was a veritable sponge, learning fast and finding my way through unimaginable experiences.”

Uzzle isn’t exactly someone who can sit still for long, however. He took his education, and he kept looking forward.

“With LIFE, and later with Magnum, the theology of the institution can become entangling and aesthetically confining,” he explains. “I’ve always needed freedom to be a bit on the wild side, to climb out on those limbs of career uncertainty and independently make my way and my art.”

Giving up a position as prestigious as most photojournalists could ever hope for wasn’t a decision made lightly, but creative freedom rarely beckons quietly. And Burk Uzzle is, at his core, more artist than reporter. Ever since leaving, Uzzle has worked for himself only. A few years ago, after living both abroad and across the U.S. for decades, Uzzle made the decision to set up a sprawling studio in downtown Wilson, North Carolina where he is, he says, the happiest he’s been in his whole life. He left North Carolina at 20 and didn’t return until he was 70.

North Carolina is home,” he says simply. “I identify with the culture, the landscape, and both the warmth of the people and their eccentricities.

Part of what’s making Uzzle so happy here is that he is busier than ever today. A documentary, “f/11 and Be There”, is being made about his life, and his latest photography projects are ongoing. Uzzle left New York for his home state specifically to document the people and landscape here, and that’s exactly what he’s doggedly spending his days doing.

Most recently, Burk Uzzle has been methodically producing a portrait of North Carolina to live alongside his preexisting body of work, which is already hardly less than a veritable anthology of the last century. He captured Borneo, the Cambodian and Vietnam wars, MLK and the Civil Rights Movement, and Woodstock, to name a few.

Six decades into this whole photography thing, he shows no sign of slowing or of backing down. By chronicling the culture of the African-American community from the area in which he himself grew up, and with his exhibition titled “Perceptions and Recognitions: African Americans of Eastern North Carolina”, Uzzle has unmasked everyday people in extraordinary fashion.

“African-American culture has always been a muse for me,” Uzzle tells us. “When the Greenville Museum of Art invited me to produce a new body of work for an exhibition, it extended my reach into the community I had been photographing since returning to North Carolina.”

With the museum, Burk Uzzle also came to the conclusion it would be important to show the twenty pictures he took in 1968 of the death and funeral of Martin Luther King Jr. This larger composition about race and humanity is, for Uzzle, a timely and important discourse.

“It’s just what this damn country needs,” Uzzle says plainly. “People getting along.”

Art and journalism meet for Uzzle here again, and his visually-dazzling surrealism is in full display with each piece from the exhibition: Congregation Ladies, a picture of the churchgoers of today’s South, and his eerie portrait of North Carolina native Dr. Alma Cobb Hobb.

Though he’s seen all iterations of photography over the years, Uzzle has switched over to all digital. He wouldn’t go back to film, either, professing a love for the way digital has allowed him to reimagine photography.

“Doing something new keeps me young.”

And with that spirit, and with a legacy so looping and winding, does Uzzle have a favorite moment, a highlight, a memory that surfaces above the rest? The answer is telling of the man himself—despite all the international travel, prestige, and presence at major world events, Burk Uzzle has been, and remains, dedicated to the nuance of everyday life.

“I would be doing a disservice to my many wonderful subjects without referring to them all as the highlights of my life,” he says plainly. “I just look forward to whatever the next day brings.”

SOCO Gallery in Charlotte carries Burk Uzzle’s work, and f/11, due on screens soon, ended production in April of 2017.