After decades of dabbling in art of various kinds, it was nearly four years ago when Julio Gonzalez created a project he’s called Dia de los Casi Muertos. The effort struck such a chord that it ultimately changed Julio’s course: He is serving as the McColl Center Artist-in-Residence through August of 2018 from his second-floor studio in the Uptown gallery.

Gonzalez moved to Charlotte as a young teen, where he worked tirelessly in his father’s restaurants all across the region, from High Point to Rock Hill. Still, he says, he has “always been an artist.”

“I’ve drawn for as long as I can remember. In middle school, I started drawing my own comics with my own characters. But I had no interest in art history — I just wanted to write stories and draw.”

For many years, art was an “in-between thing” for Julio as he pursued other work, but then his multi-year Dia de los Casi Muertos (Day of the Almost Dead), was born. In it, Julio reacted to what he initially perceived as a growing cultural appropriation of the Mexican Day of the Dead holiday. It struck him as noteworthy, and he wanted to react.

Julio began adorning subjects with head-to-toe skeletal body paint, making full-body photographs, and then conducting interviews with people about death — their own and others. He got such an outpouring of responses that the project snowballed into something much bigger; ultimately, it is an examination of how different cultures deal with death and the taboos that surround death and dying.

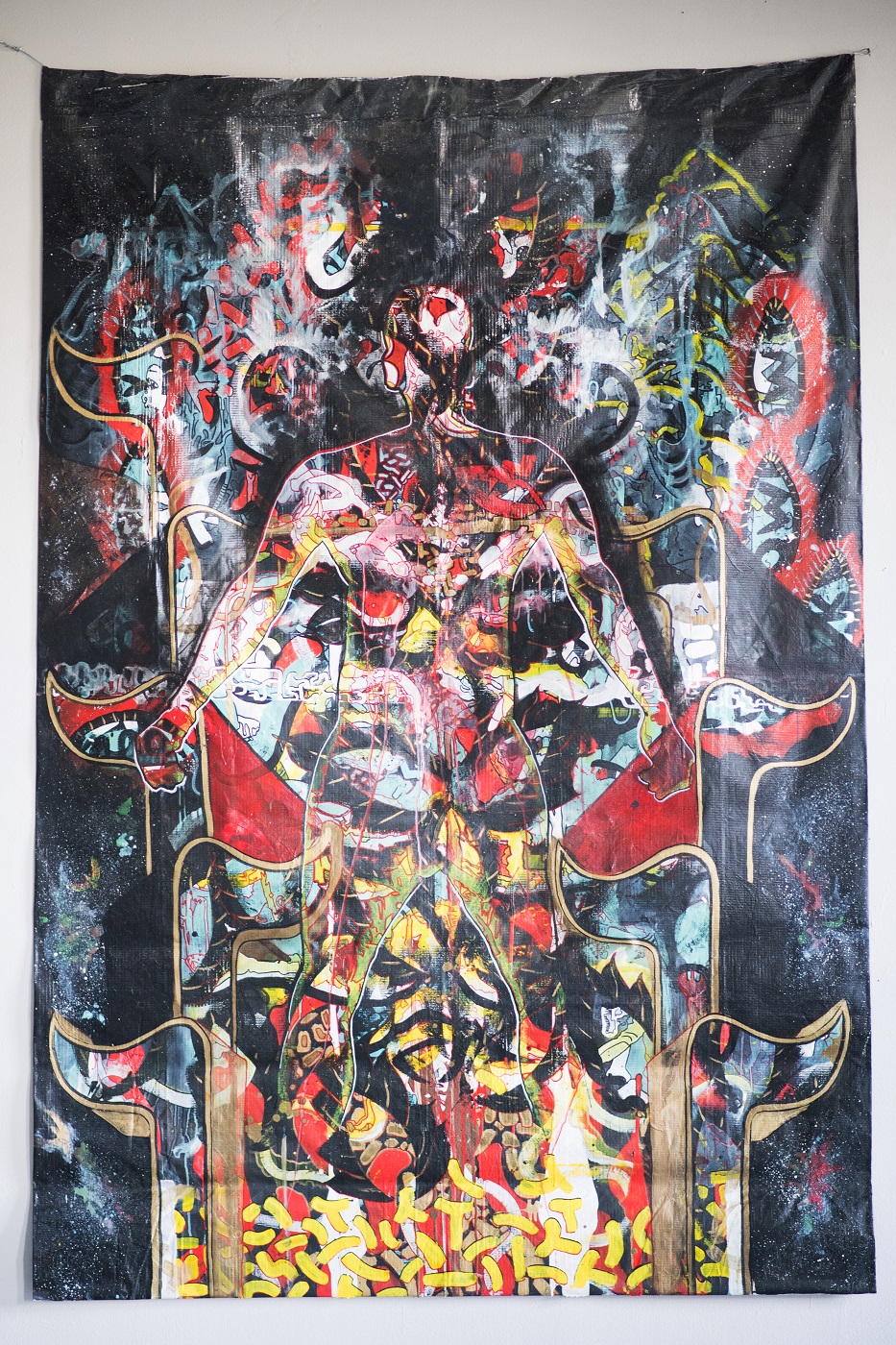

Julio Gonzalez has decided to continue to engage with the art project biannually in addition to his current work, which is focused around producing arrestingly colorful, textural multidisciplinary art at McColl.

The Artist-in-Residence is a prestigious position. How did you first get involved with McColl?

Dia de Los Casi Muertos incorporates a lot of elements and was getting to the point where I could not create it out of my spare room anymore. At the time, I was just dipping my toe into getting grant funding. My friend looked over my draft and said, ‘Julio, your concept is strong but this proposal is sh**.’ He said the next time we spoke, my revised proposal should be something worthy of submitting to a cultural organization like the McColl. So that’s what I did, and here I am.

Since Dia is partially about cultural practices, how has your own heritage influenced your work?

Who am I? Where do I come from? Where am I going? These are the basic questions we all ask ourselves. I grew up as a Latino in the South during the 80’s. My brothers are mixed race. From this point of view, the question of heritage get tricky: Am I Honduran? Am I Mexican, am I American? I grew up watching Sabado Gigante on Univision with my grandmother while also watching Thundercats during Saturday morning cartoons. Trying to figure out my identity lead me to always see things from multiple perspectives.

Did you go to school for art?

I don’t have any formal art training. I started working to earn money as soon as I could, and at my dad’s restaurants I started as a busboy and eventually worked every position from dishwashing to the accounting office. I took up DJ-ing on the side for a few years, too. I would draw on the back of tickets or bar napkins when the restaurant was slow.

As a self-taught multidisciplinary artist, what are some of the greatest lessons you have learned about being an artist?

Try to make art you enjoy and find your tribe.

You describe your artistic practice as constantly asking ‘what if?’ What has been a memorable ‘what if’ question?

I’m currently working on a body of work that is inspired by pre-Columbian culture. As I was researching Mayan writing and architecture, I began to wonder ‘what if they had not experienced a decline and had continued as an empire?’ What would they have created with new technology and processes like 3D printing and knitting for example? The answers are currently on display at the McColl and Bechtler Museum of Modern Art.

What is your creative process like?

Mentally, I’m always absorbing. I always keep a sketchbook with me. it’s full of drawings, notes, and checklists. I have all of them, going back to middle school. I will usually have one main project and a lot of experiments going on at the same time. If I get stuck on the project, I can switch to one of the experiments until I get unstuck. Right now, there’s nothing on the backburner — Everything’s cooking all at once.

What message do you hope to express through your art?

I’d like people to stop and think, to realize how connected we are to one another. And I’d like people to unashamedly go back to that sense of curiosity, exploration, and childlike wonder.

You do a lot of great things in the community. How important is that sense of community to your work?

Being out in the community is vital to my artistic practice. It started back when I was a kid sneaking around tagging graffiti on walls as a way to get my voice out in the community. That morphed into murals, which then led to the work I’m doing now. I’m less concerned with getting my voice out there with the community work, rather it’s about using my art as a vehicle to express a community’s voice. I get the joy of helping make that happen.

What is your favorite thing about having a career in art?

I love that there are no rules and no guarantees. It’s wide open.

You can find Julio’s work on display at McColl and Bechtler Museum of Modern Art, and you can visit him at McColl as he serves the rest of his term there.