Inside Scott Avett’s art studio in Concord, NC, we got a glimpse into his creative mind, from the songbook to the canvas. As he’s made a name for himself through music and The Avett Brothers, he has maintained a connection to his visual art that’s been unshakeable. This is the artistic expression that he says feels most primary, while music has required more effort. Already known widely as a prolific creator, this is a look into the art of Scott Avett in a brand new way.

On The Farm

It’s a late July day in Concord, North Carolina, the heat rising with steamy steadiness alongside the climbing sun. Farms and ranch houses assemble around us, making a mosaic as far as the eye can see. From the mouth of a short gravel driveway, Scott Avett comes into view, stooping to pet a tongue-lolling, summer-cut Old English Sheepdog. Straightening up with his furry companion beside him, he offers a little half wave to mark our passage onto the picturesque piece of Piedmont he owns here in his hometown.

With a wood-stacked open barn, scrubby grass washed yellow from the heat, even a shining pickup truck waiting, it’s exactly the sort of place you’d expect to find the elder Avett on any given weekday morning. Well, you might had The Avett Brothers never happened.

Nowadays, it’s a bit more of a rarity to find Scott at home with a few hours to spare. Still, you get the feeling Scott would have found himself in the same spot, with the same trappings, no matter what future unfolded. Even as the band’s success has steadily grown, it doesn’t appear that much of Scott’s private life has been nudged along by the gilded hand of fame. As a friend walks by at one point, Scott asks,

Hey, did you find that chicken…?

Younger brother Seth Avett lives less than a mile down the road, and their parents are nearby, too. Scott’s is a life intentionally inseparable from the land that surrounds him today and the stories it holds, even if his day job might have lead you to envision him residing somewhere more… rock n’ roll.

The origins of the group that has largely defined Scott’s adult life date back to 2000, when he and Seth both shelved other musical projects and began playing together under “The Avett Brothers” name. The simple monniker called out something growingly evident: Theirs is a sum greater than its parts, knit together by the bond that lets them share a name.

Scott and Seth are arbiters of a musical prowess realized in childhood (perhaps even before, if you believe in that sort of thing). ‘Round here in Cabarrus County, music has leached into the water. George Clinton was born here, and the Avetts signed onto their first record label with another Concord native, Dolphus Ramseur of Ramseur Records, with whom they maintain a relationship to this day. Father Jim Avett is a gospel/country artist, their sister, Bonnie, sometimes joins the boys on stage, and the North Carolina native, late bluegrass legend Doc Watson encountered Seth when the youngest Avett was a mere 14-years-old. This is a breeding ground for folk and country, but in the brothers it birthed something entirely new.

Fast-forward two decades, and you’re looking at a group rounded out by bassist Bob Crawford and cellist Joe Kwon. Together, The Avett Brothers have released an impressive sixteen albums (a seventeenth forthcoming October 2019), garnered three Grammy nominations and a Gold album in 2009’s I and Love and You. That album was the beginning of their joined forces with Rick Rubin, one of the most prolific and legendary producers of our time. The co-founder of Def Jam Recordings and producer of everyone from Run DMC to Justin Timberlake and Johnny Cash is effusive about the Avetts; he’s called their music “completely unique and original.” On top of all that, their real bread and butter is the grueling touring schedule they maintain, hitting the road year after year after year for ever-swelling crowds. Even with artists’ souls, they seem to have been unable to shake that old farmer work ethic.

But the band’s not the end of the story. That lazy type of reticence to allow performers to fit into more than one box is defied wholesale by Scott’s obsession with story-telling and the metering of human experience through artistic measure. His interests carry beyond the stage and the songbook, and as he tells it, always have.

“I’m not anything first—not painter, musician, writer, printmaker, performer—before I am an artist,” Scott once said simply. But, he added, “I am always thinking in visual terms… Even when I’m writing, I’m thinking visually, and I feel like everything trickles down from that.”

Rounding the corner past the barn, Scott leads us into his art studio.

An Artist’s Roots

Late summer 2019 marks a time when Scott’s work is about to hit a new crescendo. Alongside a calendar full of touring, his painting and printmaking, longtime complements to the music, have been keeping him particularly busy. Preparation is in full force as the North Carolina Museum of Art gets ready to open Scott’s first ever solo exhibition, I N V I S I B L E, on October 12.

The NCMA show, set to run through February 2, 2020, marks a special moment, when the art reflecting a period of Scott’s personal life, spanning two decades, can come together in one place—and his home state no less.

His work is sometimes abstract, like his journal excerpts, but often figurative, playing with faces, features, and movement. Scott says he has “no way to know how to describe” his particular style.

“I figure making the images is my best way to explain it. My process is all about discovery… Like a good conversation with someone telling a great story that you’ve never heard, or like a great book, it’s a journey to find out something I didn’t know before. Another key element in my process is joy.”

I like my relationship with my studio to be like doodling on a scrap piece of paper; nothing critical about it, simple existence.”

Over the decades, while The Avett Brothers were allowed to take center stage, Scott kept his visual art a quieter and less readily consumable province, not quite entirely solitary but not nearly as public. The impetus for his visual art—mostly manifested now in acrylic, silkscreen printing, and oil painting—dates to his youth. In the Avett household growing up, art, like music, was all around.

“Dad drew some very funny [pictures]… In fact, most of our church sermon time was spent drawing cartoons of members of our church body and laughing. And Seth is a visual artist, too. He’s a brilliant draftsman and very gifted at caricatures.”

During schooling, a sixth or seventh grade art teacher encouraged his efforts, and then later, while earning a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from East Carolina University, a few notable professors (Leland Wallin, Scott Eagle, and Michael Ehlbeck) echoed the notion that art could be something careerist for Scott. He’s continued the endeavor ever since. Which came first—visual art or music-making—seems immaterial, or at least has now become too blurrily transposed in his memory to parse.

Many of the same themes (love and longing, contemporary life, spirituality) that capture his imagination in writing lyrics surface in the paintings and prints, too. I N V I S I B L E is a fitting cross-section of what makes Scott’s creative mind whole: The richly textured, often brightly colored prints and paintings contain nuanced lifelines to his family, his Southern upbringing, and the music, too. His subjects, in song and on canvas, aren’t tethered to the medium: All of Scott’s art tends to explore the emotionally charged, vulnerable, and nakedly truthful. You’re allowed to peer at snippets of personal moments—sometimes in the form of literal diary excerpts—that contain within them overarching universal narratives.

That’s part of what is so appealing about the Avetts’ work to their many fans: Their willingness to mine their own most personal moments and intimate observations creates a sense that not only do you know what they’re going through, but they might understand you as well.

“I have faith that my personal experiences are familiar, in some way, to all other humans,” says Scott. “In other words, that [my experiences] connect. I also trust that any social, political, and or spiritual ‘truths’ that I possess are present in my work.”

Over the years, he has exhibited his work in New York and St. Louis, among other cities, and his art has been purchased by several prominent private collectors. A close relationship with Chandra Johnson of Charlotte’s SOCO Gallery—a place he calls a “beacon” for North Carolina’s art scene—helped solidify him a spot to show his work close to home.

”I knew Scott first as a musician then as a friend,” Chandra says. “His visual art was a huge discovery as this was a creative pursuit he kept private for many years. After seeing his work and hearing about his practice, I felt strongly about bringing him into our gallery program. I have enjoyed watching Scott’s career as a painter unfold.”

There have been a lot of others throughout the years, too, and Scott is quick to acknowledge their influence on his abilities, a habit honed perhaps by decades of the collaborative, shared nature of band members. (Every song is attributed to “The Avett Brothers” rather than in individual credits).

“I have received encouragement from many, and I have used it to its fullest. An artist and dear friend, Eric Fischl, many of my peers, and all of my family have helped guide me in knowing who I am,” Scott explains. “Since the time I met Eric in 2015, I have made more work than in the previous fifteen years. His encouragement, artist to artist, means the world to me. And Tom Shulz, an artist based in Asheville, was so unbelievably supportive of my work at a very early stage; He worked very hard to assemble teams to help me show work in ways I wanted to, and I am forever grateful for that.”

A Oneness

Inside the modest ranch—Scott’s workspace and studio—are an unfinished few rooms, replete with paint-splattered plywood floors and a lofted upstairs. The little ranch’s most defining characteristic is the sprawl of artistic detritus—buckets of paint brushes, dried kaleidoscopic palettes, oil paint tubes, and scraps of paper proliferate across any surface that can hold them. Doodles are tacked to the walls, half-thoughts scribbled haphazardly with pen on a cupboard door. Stacked against the walls, like well-ordered books on a library shelf, are canvases upon canvases, so many that walking from room to room has become a delicate maze. In varying sizes, picture-frame to ceiling height, each was built by Scott by hand.

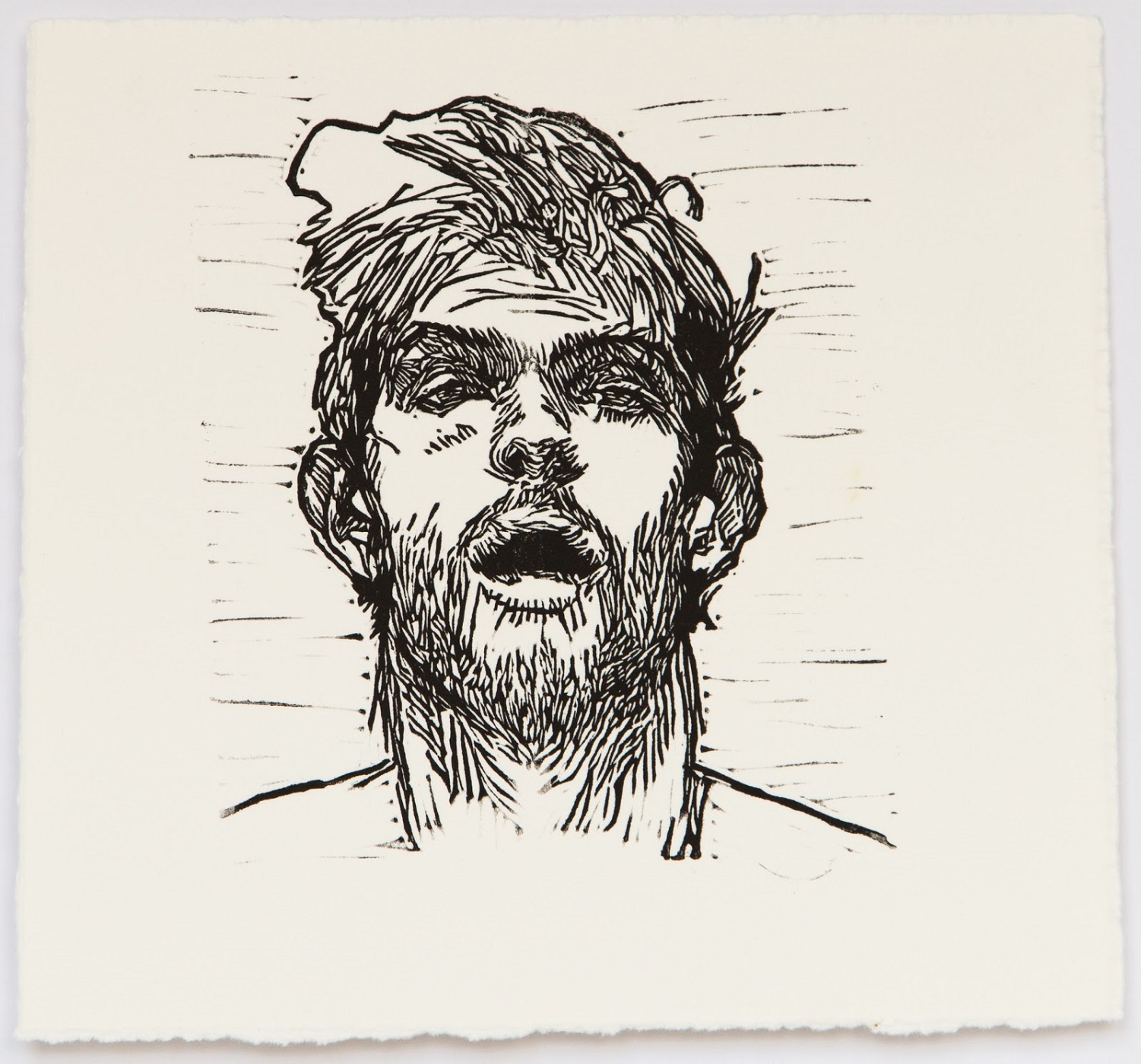

Some of the art looks surrealist and cartoonish, like a gaping clown face, and others strikingly lifelike. From one corner, the artist himself, in self-portraiture, gazes into the ether, as does the image of one of his young sons, rendered almost true to size. Dozens of other canvases lean in upon their closest mate, their stories clandestine if only for now.

Much of the art housed here is rendered in staggeringly large scale, made by an artist seemingly willing to unfold the less public side of his life with no equivocation. You can see Scott’s wife, looking exhausted while bouncing a wailing baby. His older child, in pajamas, brushing his teeth over a sink. A baptism is performed by a serious-faced priest.

The tendency to bare their souls is almost reflexive for the Avetts at this point; Scott’s visual renderings contain every bit the depth of emotionality that the Avett Brothers’ productions have become synonymous with. Indeed, The New Yorker noted The Avett’s “extreme musical honesty” and, in a 2013 Rolling Stone interview, Rick Rubin explained, “The first thing that struck me was the sincerity in their vocals. I really believed them… They feel life in a deep way.”

All around us in the studio is the continuity of those proclivities: The visual art of Scott Avett is not that surprising of a departure from his music, nor is it unclear how he holds the two in tandem—It’s all like one broadcast of artistic consciousness, with a few different channels.

“Music always felt like a ‘look at me!’ or ‘listen to me!’ type of endeavor,” Scott says, “where painting and printmaking is like, ‘look at this!’ or ‘look what I made!’

I love doing both: I always loved show and tell, and I always loved attention.

Scott does seem as comfortable here in the studio as on the stage, a man naturally performative and used to gleaning inspiration from both the banal and the extraordinary in his immediate surroundings. How it will manifest—a song lyric, a photograph, a sketch—well, each seems equally likely. As we stand around, perched carefully so as not to knock anything over, he’s generous and thoughtful with his descriptions of each piece, pulling out one after another, enthusiasm tangible.

The other clear thread in Scott’s life work is, unglamorous though it might sound, volume. It’s been said that the essential step to making art is to simply show up, and that’s clearly an element with which Scott doesn’t struggle. On the contrary, he’s a pursuant of a seemingly endless production of music and visual art. The studio is almost literally overflowing with art, while plenty more lives elsewhere, in homes, galleries, and collections. As he’s putting the finishing touches on the NCMA show, he’s also getting ready to release that seventeenth Avett Brothers album and has been logging hours in the studio with another record he produced, performed, and co-wrote on with the band Clem Snide. That one is due out early 2020.

It all starts to sound a little… head-spinning. For a man on the road touring more than half the year, and with three young children and a partner at home, keeping time on his side sounds like a full-time job itself.

But Scott seems nonplussed by the idea, shrugging off any implication that his cup might runneth over.

“Simply put, I try not to waste time,” he says. “And I prioritize the practice of doing nothing when it is right. I feel a surplus of time when I’m in this practice.”

Fair enough, but voluminous creation doesn’t always mesh well with the fleeting type of inspiration that visits artists.

“I have some ideas that come in a flash, and often I do nothing with them even though I know they are beautiful,” Scott muses. “I trust that the true ideas will stick with me and eventually be made. I also think inspiration is very ghostly in the way that the conceptual idea of something may not even exist for me until after I’ve made a picture… In this regard I could randomly flip through ideas or visions in my life and just draw one. The next thing I know, there is a very mysterious and interesting image on canvas. In other words, just like doing nothing is the answer sometimes, other times just doing something, literally whatever, is the answer.”

The Making

Back in the biggest room of the studio, natural light streams in and a chair sits smack in the center of the floor, angled toward the one painting that’s on display. Scott sits here sometimes just to take in where he’s at in the process of piece. Today, it’s the baptism painting, half still in sketch and half filled in, that’s on the easel.

“At this point, I am interested in the unification of all things,” Scott is explaining. “My visual work, as well as any song I write, has to partake in unification or it is not interesting to me. In this regard they, song and picture, are from the same stream.

I have to prepare myself to be painter and singer in different ways… The expressions are coming from the same place, but the vulnerabilities show up in different ways.

There are a few windows frames laying about, too, relics Scott found from the house he grew up in. Fascinated by the form and the memories they held, he replaced the glass with plexi and inserted a screen-printed, cut-out image of his young son doing a cartwheel-handstand type maneuver. He’s already churned the image out in several other iterations, too, “pushing it” over and over again to see what he could create. It’s an image he says will be with him all his life, and the old Avett home windows will come to rest all across the country, housed in different galleries.

He perches on the worn chair for a bit, initially for a few portraits, moving aside a little childhood tooth fairy pillow hand-stitched by his mother so he can settle in. Looking ahead at the in-process canvas, he stays put longer than needed for the camera’s demands, ruminating aloud on the direction he plans to take the unfinished image.

Before long, Scott hops up to ask if we want to see another piece from the stack behind him. It takes two people to haul out a canvas that grazes the ceiling once righted.

In earthy, warm tones of green and gold, his young sons come into focus; with rounded bellies and hands grasping, they wade in a pond on the Avett property. It’s richly textured and full of movement, breath, and childish energy. Scott’s paintings, in their intimacy and specificity, are like tangible versions of eidetic memories: At any moment, it looks like the boys could spring to life, noisy and splashing.

In its scale alone, it’s clearly a canvas Scott logged many hours on. How, one of us wonders aloud as we look on, did he know when the piece was “complete”—or for that matter, when to be done on any one of them?

“If I remove myself and my ego from it, whether it’s good or not, then I can see how it was great a long time ago,” Scott says. “It can be great a lot of ways but it will only be great in one way. That’s really important, same with songs. There’s maybe an infinite amount of ways that a song can turn out exactly like it’s supposed to, but it’s only going to turn out one. Until you’ve stamped it and it’s gone, you really don’t know… So I just paint and then move on. And sometimes I overthink it and don’t stop when I should have.”

To this point, he pulls out another smaller piece, laughing as he recalls painting it in colors he says he shouldn’t have, to the point in which a buyer, interested in the original, unpainted form, turned down the purchase when he saw the final product as it lives today.

“See,” he gestures at the painting in his hands. “There are ways that it can not be great as well—there’s probably more window for that, for it to be dishonest. The painting—it told me. I should have stopped, but I didn’t have the confidence… or maybe I wanted something more out of it. The life of the painting, if I try to perfect it, just starts to die or turn into a representation of the image which is less…” he trails off, looking at it.

It seems that inherent challenge is part of what drives Scott, rather than defeats him, which may be part of the secret of his ability to churn out so much damn art. Rather than meditating on perfection or lamenting an overflowing schedule, he shows up and works.

“Artists are like spiritual teachers in that they are computing mysteries in front of people… It’s the same singing a song, especially when you aren’t a great singer, because you’re finding the pitch and finding your sound in front of people.

The struggles have always made the best art. I get pretty bored with what most people call masterpieces because ‘domination’ of a medium is not what it’s about. It’s about going so far that you lose all control and then people see your “unguarded” soul, your real humanness. That’s really art to me.

Onward

As we’re wrapping, extending thank yous and chattering on everything from CrossFit (Scott says incorporating exercise on the road has helped his vocal abilities) to his kids heading back to school, Scott asks, do we want to see the upstairs?

“It’s part of it,” he offers.

Unsure what else there is to see, we file up the narrow staircase that cuts through the profusion of art and its remnants to see that Scott has cleanly sectioned off a small recording studio. The walls are sound-proofed (in part with a thick moving blanket tacked up like a curtain) and its dimly lit. A piano absorbs one entire wall, and two guitars hang nearby. Scott’s framed Gold album is here, too.

Standing upstairs, you can look out over a little balcony that opens up over the paint splattered floor and chair below where Scott just sat for us. Up here, there’s not so much as a stray paintbrush: Housed within one space is a nice, cleanly sliced divide. The upstairs exists as the missing piece to the studio below, the unabridged version of Scott’s art.

With the ease surely born of muscle memory, he drops down into the piano seat, and, in another act of generosity, performs for us a single song. It’s not fancy up here but the music swells with spot on acoustics.

He mentions the work he’s been doing up here recently: The Avett Brothers album coming in October, and the Clem Snide project. This fall, he says, there will be a lot of shows to play.

“I’m having so much fun performing for and connecting to people on that realm.”

Before the solo exhibition opens at The North Carolina Museum of Art in October 2019, Scott’s art will be at the Seattle Art Fair and at William Shearburn Gallery in St. Louis, with Q&A’s at select cities along the way.

And that’s it; we exit through the porch of the little ranch, dumped back out into the scorching sunlight to return Scott to his many orders of business.

“It’s a gift; the fact that I’m able to do this is a total privilege,” Scott says. “I have no clue how it was able to happen, I just know that it’s a gift from an order of events and a higher power that I can’t explain. My parents started that by just protecting our time, saying, “You go to school. And if you don’t want to go to school, go to work and be best at whatever you do, whatever it is.”